Notation and Conventions¶

Given multiple overlapping images \(\{z_1({\bf r}), z_2({\bf r}), ...\}\), we designate by \(R({\bf r})\) the set of image indices that overlap a point on the sky \({\bf r}\). We assume that all images have already been resampled to a common coordinate system and common photometric units. Each image is related to the true sky \(f({\bf r})\) via its point spread function (PSF) \(\phi_i({\bf r}, {\bf t})\) by

It will be convenient to rewrite this integral as a sum, and hence define the PSF and sky as discrete quantities rather than continuous functions (note that \({\bf r}\) already only takes discrete values). The true \(f\) has power at arbitrarily high frequencies, so we cannot simply sample it on a grid. But the PSF does not; we can always choose some grid with points \({\bf s}\) upon which we can sample the PSF and exactly reconstruct it with Sinc interpolation:

We can then insert this into (1), and reorder the sum and integral:

This lets us identify the sinc-convolved sky \(h\) as

Note that \(h\) contains all in information about the true sky, and hence we can use it instead of \(f\) to form a discrete analog of (1):

We will use this form for the remainder of the paper.

We assume all images have Gaussian noise described by a covariance matrix \(C_i({\bf r}, {\bf s})\). Because astronomical images typically have approximately uncorrelated noise only in their original coordinate system, we should not assume that the covariance matrices in the common coordinate system are diagonal.

This notation uses function arguments for spatial indices and subscripts for quantities corresponding to different exposures, but (as described above) this does not imply that the spatial indices are continuous. The spatial variables (typically \({\bf r}\) and \({\bf s}\)) should be assumed to take only discrete values, and indeed we will at times use matrix notation for sums over pixels (in which images are vectors, with the spatial index flattened):

In matrix notation, (2) is simply

Note that in matrix notation we continue to use subscripts to refer to exposure indices, not spatial indices; at no point will we use matrix notation to represent a sum over exposure indices.

We assume the true sky is the same in all input images (i.e. there is no variability). This is clearly not true in practice, but coaddition algorithms are explicitly focused on capturing only the static sky.

Lossy Coaddition Algorithms¶

Direct Coadds¶

The simplest way to build a coadd is to simply form a linear combination of the images that overlap a point on the sky. The coadd image \(z_\mathrm{dir}({\bf r})\) is then

where \(w_i\) is an arbitrary weight for each image, defined to sum to one at each point. We cannot assume the weights are constant over a single input image; this would make it impossible for the weights to sum to one on both sides of a boundary in which the number of input images changes. It is equally important that the weight function vary only on scales much larger than the size of the PSF; without this it the coadd has no well-defined effective PSF. The weight can be chosen to optimize some measure of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) on the coadd, popular choices include

to optimize the average per-pixel SNR and

to optimize the SNR of a point source. In both cases, \(\sigma^2\) is some spatially-averaged scalar reduction of \(C_i\), while \(|\phi_i|^2\) is the inner product of the average PSF (and the inverse of its effective area).

If the weights are proportional to exposure time and the input images are observed back-to-back, the direct coadd is mathematically equivalent to a single longer observation in the limit of perfectly linear detectors.

The effective PSF on the coadd and pixel covariance matrix are simple to compute:

These quantities would be many times larger than the coadd itself if evaluated on every pixel, making direct evaluation impractical. They are discontinuous at the boundaries of input images (and masked regions within them), making interpolation problematic as well.

The solution we have adopted for PSF models has been referred as both CoaddPsf (from lsst.meas.algorithms.CoaddPsf) and StackFit (after the shear estimation technique where it was developed), and is essentially a form of lazy evaluation. When a PSF model image is requested at a point, we simply evaluate the PSF models for all of the input images at that point, transform them to the correct coordinate system, and compute the weighted sum on demand. We typically assume that the PSF is constant over the scale of a single astronomical object, and hence this reduces the number of PSF model evaluations from the number of pixels to the number of detected objects. When an object lies on a boundary or a region with masked pixels, the true PSF is discontinuous and the constant-PSF assumption is not valid. At present, we simply flag objects for which this is true, but this may not work when the number of input images is large; in this regime the number of border and masked regions increases, though the severity of the discontinuities decreases as well.

Our current approach for coadd uncertainty propagation is to compute and store only the variance. We will likely expand this in the future to storing some approximation to the covariance (e.g. by modeling it as constant within regions where the number of input images is constant).

Direct coadds are lossy, requiring some trade-off between image quality (PSF size) and depth (SNR). This can be easily seen from (4): including an image with a PSF larger than the current weighted mean PSF always increases the size of the final PSF, regardless of the depth of the new image.

PSF-Matched Coadds¶

In PSF-matched coaddition, input images are convolved by a kernel that matches their PSF to a predefined constant PSF before they are combined. If \(\phi_\mathrm{pm}({\bf r})\) is the predefined PSF for the coadd, then the matching kernel \(K_i({\bf r}, {\bf s})\) is defined such that

Typically \(K\) is parametrized as a smoothly varying linear combination of basis functions. The details of fitting it given a target coadd PSF and input image PSF models is beyond the scope of this document; see e.g. [Alard1998] for more information.

Because deconvolution is (at best) noisy, convolution with \(K_i\) will generally increase the size of the PSF. This highlights the big disadvantage of PSF-matched coadds: the images with the best seeing must be degraded to match a target PSF whose sizes is determined by the worst of the images to be included in the coadd. Thus PSF-matched coadds must either include only the best-seeing images (sacrificing depth) or suffer from a worst-case coadd PSF.

After PSF-matching, the coadd is constructed in the same way as a direct coadd:

The PSF on the coadd is of course just \(\phi_\mathrm{pm}({\bf r})\), and the pixel covariance on the coadd is

Typically, the covariance terms in the uncertainty are simply ignored and only the variance is propagated, though this can result in a signficant misestimation of the uncertainty in measurements made on the coadd.

Outlier Rejection and Nonlinear Statistics¶

A common – but often misguided – practice in coaddition is to use a nonlinear statistic to combine pixels, substituting the weighted mean in (3) and (5) for a median or sigma-clipped mean. The goal is to reject artifacts without explicitly detecting them on each image; the problem is that this assumes that the pixel values that go into a particular coadd pixel are drawn from distributions with the same mean.

This is not true when input images have different PSFs, as in direct coaddition. Building a direct coadd with median or any amount of sigma-clipping will typically result in the cores of brighter stars being clipped in the the best seeing images, resulting in a flux-dependent (i.e. ill-defined) PSF. Even extremely soft (e.g. 10-sigma) clipping is unsafe; the usual Gaussian logic concerning the number of expected outliers is simply invalid when the inputs are not drawn from the same distribution.

The presence of correlated noise means that even PSF-matched coadds cannot be built naively with nonlinear statistics. In PSF-matched coadds, all pixels at the same point are drawn from distributions that have the same mean, but they are not identical distributions. As a result, nonlinear statistics do not produce an ill-defined PSF when the inputs are PSF-matched, but their outlier rejection properties do not operate as one would naively expect, making it hard to predict how well any statistic will actually perform at eliminating artifacts (or not eliminating valid data). Nonlinear statistics also make it impossible to correctly propagate uncertainty to coadds, as long as they are used to compute each coadd pixel independently.

Optimal Coaddition Algorithms¶

Likelihood Coadds¶

An optimal coadd is one that is a sufficient statistic for the true sky: we can use it to compute the likelihood of a model of the true (static) sky, yielding the exact same computation as if we had computed the joint likelihood of that model over all the input images. This joint likelihood is thus a natural starting point for deriving an optimal coadd.

The log likelihood of a single input image \({\bf z}_i\) is (in matrix notation)

The joint likelihood for all images is just the product of the per-image likelihoods since the images are independent. The joint log likelihood is thus the sum of the input log likelihoods:

By expanding this product, we can identify terms that include different powers of \({\bf h}\):

with

These three terms represent a coadd of sorts. \(\boldsymbol{\Psi}\) is an image-like quantity, and \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) behaves much like an (inverse) pixel covariance matrix. Together with the scalar \(k\) these are a sufficient statistic for \({\bf h}\), and hence we can think of them as a form of optimal coadd, albeit one we cannot use in the usual way. In particular, the covariance-like term \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) does much more than just carry uncertainty information, as it captures what we typically think of as the PSF as well. We will refer to the combination of \(\boldsymbol{\Psi}\), \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\), and \(k\) as a “likelihood coadd”.

The fact that we cannot interpret a likelihood coadd in the same way as other astronomical images is inconvenient, but the real problem lies in its computational cost: \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) is extremely large; while it is sparse, even just its nonzero elements would consume approximately 200GB in single precision for a single-patch 4k \(\times\) 4k coadd. While the same is broadly true of any detailed attempt to capture coadd uncertainty, \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) has even more nonzero elements than \({\bf C}_\mathrm{dir}\) or \({\bf C}_\mathrm{pm}\), and it plays a much more important role. Approximating \({\bf C}_\mathrm{dir}\) and \({\bf C}_\mathrm{pm}\) generally implies incompletely or incorrectly propagating uncertainties, generally by a small amount, while approximating \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) also implies incorrectly modeling the PSF.

Kaiser Coadds¶

If the input images to a likelihood coadd meet certain restrictive conditions, an algorithm developed by [Kaiser2001] (and rediscovered by [Zackay2015]) can be used to build decorrelated coadd. These conditions include:

- The noise in the input images must be white and uncorrelated.

- The PSFs of the input images must (individually) be spatially constant.

- The input images have no missing pixels, and the coadd area does not include any boundaries where the number of input images changes.

Under these conditions, \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) has no spatial variation, giving it a particularly simple form in Fourier space:

(recall that \(C_i\) is now just a scalar, as the variance is constant and there is no covariance). Recognizing that the matrix products in (6) are just convolutions when the products are spatially constant, the Fourier-space equivalent for Kaiser coadds is

The solution is trivial (and unique, assuming a normalized PSF):

The equivalent for \(\boldsymbol{\Psi}\) and (7) is

with solution

This differs from [Zackay2015]‘s Eqn. 7 because they have redefined the flux units of the coadd to achieve unit variance on the coadd.

The problem with the Kaiser algorithm is its assumptions, which are simply invalid for any realistic coadd. While the noise in an input image may be white in the neighborhood of faint sources, most images contain brighter objects (and faint objects near brigher objects as well). In addition, the noise is never uncorrelated once the image has been resampled to the coadd coordinate system. The noise assumptions by themselves are not too restrictive, however; the Kaiser algorithm is not optimal when these conditions are not met, but we only care deeply about optimality in the neighborhood of faint sources. And ignoring additional covariance due to warping is no different from our usual approach with direct coadds.

The assumptions that the PSFs and input image set are fixed are more problematic, but this still leaves room for the Kaiser algorithm to be used to build “per object” coadds, in which we build separate coadds each small region in the neighborhood of a single object, and reject any input image that do not fully cover that region. This would likely necessitate coadding multiple regions multiple times (for overlapping objects), and it isn’t as useful as a traditional coadd (especially considering that it can’t be used for detection), but it may still have a role to play.

A more intriguing possibility is that the Kaiser approach could be used as one piece of a larger algorithm to build general decorrelated coadds. One could imagine an iterative approach to solving (6) and (7) by minimizing a metric such as

where \(\boldsymbol{\phi}_\mathrm{dec}\) is parametrized as a smoothly-varying interpolation of a set of kernel basis functions, and \(\lambda\) controls how strongly off-diagonal elements of \({\bf C}_\mathrm{dec}^{-1}\) are penalized. This is a massive optimization problem if applied to a full coadd patch, but the structure of \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) only indirectly couples pixels that are more than twice the PSF width apart; this suggests we could proceed by iteratively solving small regions independently – if we have a good guess at an approximate solution. The Kaiser algorithm provides exactly this: we can use the Kaiser method to estimate the PSF, and a diagonal covariance matrix at multiple points on the image, and then simply interpolate between them to generate our initial guess. Just imposing the Kaiser PSF (or a small perturbation to it) as the final PSF may also be feasible. This would only require us to solve for \({\bf C}_\mathrm{dec}^{-1}\) and \({\bf z}_\mathrm{dec}\), dramatically reducing the scale of the problem.

Constant PSF Coadds¶

A simple but potentially useful twist on the decorrelated coadd approach is to decorrelate only to a predefined constant PSF. This would produce a coadd with many of the benefits of a PSF-matched coadd, but with no seeing restrictions on the input images and a much smaller final PSF. Like a PSF-matched coadd, significant pixel correlations could remain in this scenario (it is unclear which approach would have more), but this coadd would enable the measurement of consistent colors and could also serve as a template for difference imaging. Both of these are cases where having improved depth and a smaller PSF in the coadd could be critical.

Having a consistent PSF across bands is the only way to formally measure a consistent color, but using traditional PSF-matched coadds for this ensures these colors will have lower SNR than model-based measurements that operate on individual exposures (which are always at least somewhat biased). If the constant-PSF coadd is instead generated using the decorrelated coadd approach, the SNR of consistent colors could be much more competitive.

The potential gains for difference imaging are even larger: the PSF size on the coadd puts a lower limit on the PSF size of an input exposure that can be differenced in it, which could require us to throw away or degrade our best images simply because we don’t have a coadd good enough to difference with it. [1] Difference imaging algorithms also become dramatically more complex when noise from the template cannot be neglected when compared with the noise in the exposure being differenced; this requires that the template have a large number of exposures. This is challenging when traditional PSF-matched coaddition is used and the coadd PSF must be optimized along with the depth, and it may be even more challenging if mitigating chromatic PSF effects requires templates binned in airmass or some other approach that effectively adds new degrees of freedom to template generation.

| [1] | The “preconvolution” approach to difference imaging decreases this lower limit (possibly to the point where it is unimportant), but is also an unproven technique. |

Coadds for Source Detection¶

Detection Maps¶

The approach to source detection in LSST is derived from the likelihood of a single isolated point source of flux \(\alpha\) centered on pixel \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\):

At fixed \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\), we can solve for \(\alpha\) by setting the first derivative of \(L\) to zero:

which yields

Similarly, the variance in the flux can be computed from the inverse of the second derivative:

The point-source SNR at position \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) is then

To detect point sources, we simply threshold on \(\boldsymbol{\nu}\), which we call a detection map. We can construct this from the components of a likelihood coadd with a crucial simplification: we only require the diagonal of \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\), making what had been a computationally infeasible method quite practical. This holds only because we have assumed an isolated point source, however; optimal detection of extended sources or blended sources would require at least some off-diagonal elements of \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\). In practice, we instead just look for multiple peaks in above-threshold regions in \(\boldsymbol{\nu}\) as defined above, and bin the image to detect extended low-surface-brightness sources.

Optimal Multi-Band Detection¶

Just as optimal detection in monochromatic images requires that we know the signal of interest (a point source with a known PSF), optimal detection over multi-band observations requires that we know both the spectral energy distribution (SED) of the target objects and the bandpass. More precisely, we need to know the integral of these quantities:

where \(T_i(\lambda)\) is the normalized system response for observation \(i\) and \(S(\lambda)\) is the normalized SED of the target source. The point source likelihood is then

with

As the notation suggests, this is just a likelihood coadd with the inputs reweighted according to the target SED, and we can similarly form a detection map from it:

In practice, the differences in throughput for different observations with the same bandpass is small enough to be neglected for detection purposes, and we could thus build \(\Phi_{\beta}\) and \(\Psi_{\beta}\) from per-band coadds of the standard \(\Phi\) and \(\Psi\). This makes it feasible to detect objects with unknown SEDs by quickly constructing detection maps for a library of proposed SEDs, and then merging those detections.

Chi-Squared Coadds¶

An alternate approach to multi-band coaddition developed by [Szalay1999] is to instead build a coadd that tests the null hypothesis that a pixel is pure sky. While [Szalay1999] does not specify fully how to handle the spatial dimensions, we can combine their method with the likelihood coadd approach above. This yields a detection map that is exactly the same as (8), but with \(\Psi\) and \(\Phi\) summed over images from multiple bandpasses. The probability distribution of \(\nu^2\) is then a \(\chi^2\) distribution, allowing the hypothesis test to be carried out by filtering on a monotonic function of the \(\nu\).

This is equivalent to setting \(\beta_i=1\) in (9), which is not the same as assuming a flat SED; in the background-dominated limit, it is actually the same as assuming that objects have the same SED as the sky. From this perspective, it is clear that \(\chi^2\) coadds are not formally optimal for the detection of most sources, but they may be close enough that detection on them with a slightly lower threshold may be more computationally efficient than trying a large library of proposed SEDs.

Quantitative Comparison¶

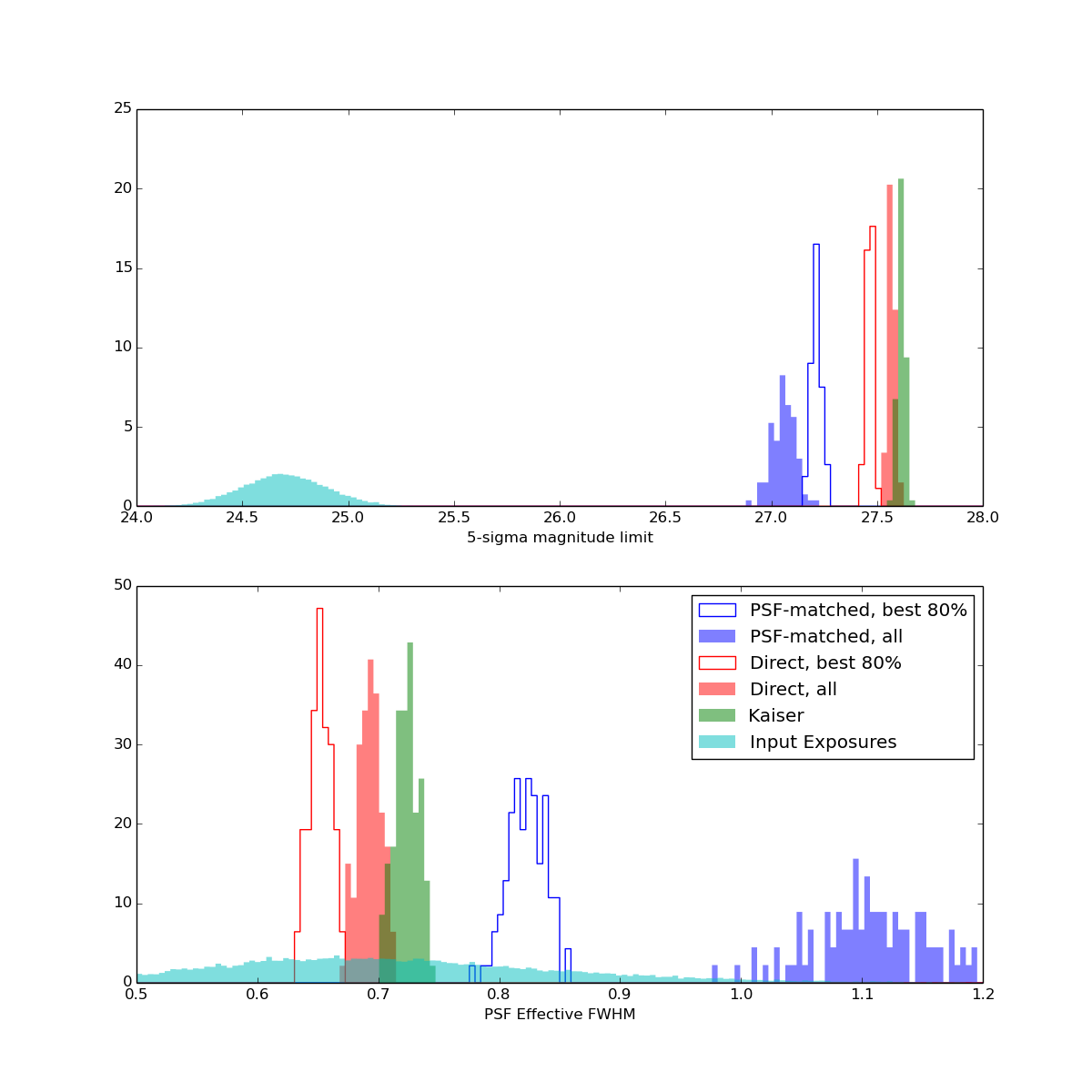

The figure above shows predicted effective FWHM (calculated from PSF effective area) and 5-sigma point source limiting magnitude for different coadd algorithms. Each data point in the histograms represents a coadd of 200 exposures, with seeing drawn from a log-normal distribution centered at 0.7 arcseconds and depth drawn from a normal distribution centered around 24.7. Direct and PSF-matched coadds are weighted to optimize point source SNR. Input PSFs use a Kolmogorov profile.

Note that the direct algorithm actually produces a smaller PSF than the Kaiser algorithm, even when the worst exposures are included (our choice of weight function strongly downweights these images). This does not mean that it contains any more small-scale spatial information than the Kaiser coadd, as it always has lower SNR. Even so, the improvement from direct to Kaiser algorithm is modest: when all exposures are included in the direct coadd, the Kaiser algorithm is only 0.1 magnitudes deeper. The improvement from PSF-matched to direct coaddition is substantial in both PSF size and depth, especially when all exposures are included. Imposing a cut on seeing percentile is clearly important for PSF-matched coaddition, but may not be important for direct coaddition, at least with the above choice of weight function.

Glossary¶

- Chi-Squared Coadd

- A cross-band coadd that is designed for detecting objects by rejecting the null hypothesis that a pixel contains only sky. See [Szalay1999].

- CoaddPsf

- A procedure for generating the PSF model at a point on a direct coadd by lazily evaluating the PSF models of the input at that point, then warping and combining them with the same weights used to build the coadd itself. Originally developed by [Jee2011] as part of StackFit.

- Constant-PSF Coadd

- Any coadd that has been designed to have a constant (spatially non-variable). This includes PSF-matched coadds, but we will frequently use this term instead as shorthand for a partially decorrelated coadd with a constant PSF, in which the noise in a likelihood coadd is only partially decorrelated in order to produce an image with a constant PSF. A Kaiser coadd is technically such a coadd, but only because it assumes constant input PSFs.

- Deep Coadd

- A lossy coadd produced using all but the very worst-seeing images. Contrast with Good-Seeing Coadd.

- Detection Map

- An image that can be thresholded to detect sources under the assumption that they are unblended point sources, formed by convolving an image by the transpose of its PSF and dividing each pixel by its variance. It can also be built by dividing a likelihood coadd by its variance.

- Direct Coadd

- A lossy coadd built as a linear combination of images with no change to their PSFs. If the weights are just the exposure times of the image, this is (locally) equivalent to a single long exposure. The PSF of a direct coadd is discontinuous at the boundaries of input images, requiring an approach like CoaddPsf to model it. This coadd is lossy, requiring some tradeoff to be made (in selecting inputimages) between depth and image quality. Noise in a direct coadd is correlated only by image resampling.

- Good-Seeing Coadd

- A lossy coadd produced using only input images with good seeing. Constrast with “Deep Coadd.”

- Kaiser Coadd

- An optimal coadd built by decorrelating a Likelihood Coadd after assuming input images have uncorrelated white noise, constant PSFs, and no missing pixels or boundaries. Origin is [Kaiser2001], an unpublished Pan-STARRS white paper. Special case of Decorrelated Coadd.

- Likelihood Coadd

- An optimal coadd built as a linear combination of images that have been convolved with the transpose of their PSFs. This procedure correlates noise, but the resulting image is optimal for isolated point source detection even if only the variance is propagated and stored (see Detection Map). For other applications (including producing Decorrelated Coadds), the full covariance must be propagated.

- MultiFit

- An approach to source measurement (especially weak lensing shear estimation) that fits the same model to all input images directly, after transforming the model to the coordinate system of each image and convolving with that image’s PSF. Formally optimal (for valid models). Contrast with StackFit.

- Proper Image

- An image with uncorrelated white noise; see [Zackay2015].

- PSF-Matched Coadd

- A lossy coadd built by combining images only after they have been reconvolved to a common, constant PSF. This either degrades all images to the seeing of the worst input images, resulting in an even harsher trade-off between depth and seeing than for Direct Coadds and more correlated noise. This is the only coadd for which nonlinear image combinations (such as a median or sigma-clipped mean) may be considered.

- StackFit

- An approach to source measurement (especially weak lensing shear estimation) that fits models to Direct Coadds after convolving with a PSF model generated using the CoaddPsf approach, developed by [Jee2011]. This avoids B-mode (and other) systematics that arise from poor modeling of PSF discontinuities, but is still lossy. Contrast with MultiFit.

- Sufficient Statistic

- Given a dataset and a likelihood that can be computed from it, a sufficient statistic for that dataset is any set of derived quantities from which the exact likelihood can also be computed. In the context of this document, an optimal coadd is defined as any coadd that is a sufficient statistic for its input images for any likelihood that assumes a static (temporily nonvariable) sky.

- Template

- A coadd used as the comparison image in difference imaging. As the template must be convolved with a kernel that matches its PSF to that of the science image, constant-PSF coadds are usually preferred, as they allow the matching kernel to be continuous.

- Zackay/Ofek Coadd

- See Kaiser Coadd; from [Zackay2015], which indepenently derived Kaiser’s result.

References¶

| [Alard1998] | Alard & Lupton, 1998. A Method for Optimal Image Subtraction. ApJ, 503, 325. |

| [Szalay1999] | (1, 2, 3) Szalay, Connolly, & Szokoly, 1999. Simultaneous Multicolor Detection of Faint Galaxies in the Hubble Deep Field. AJ, 117, 68. |

| [Jee2011] | (1, 2) Jee & Tyson, 2011. Toward Precision LSST Weak-Lensing Measurement. PASP, 123, 596. |

| [Kaiser2001] | (1, 2) Kaiser, 2001. Addition of Images with Varying Seeing. PSDC-002-011-xx. |

| [Zackay2015] | (1, 2, 3, 4) Zackay & Ofek, 2015. How to coadd images? II. A coaddition image that is optimal for any purpose in the background dominated noise limit. arXiv:1512.06879 |